Top image: a group of moran, young men warriors. The topography provides many lookouts to watch livestock or security matters below. Image credit: Spidylolo, CC BY-SA 4.0 license

Monique’s tribe, the Samburu, are a group of the Maasai (Maa-speaking) group of tribes. Their home is in the very large Samburu County in Kenya’s cool northwest highlands, near the Great Rift Valley. Their most famous “relatives” are the southern Maasai. (There is a long rivalry over who are the most authentic, “real” Maasai: the Samburu definitely believe it is them, and take much pride in their traditions and culture.) They are historically quasi-nomadic pastoralists: herdsfolk who move around when it’s useful to help their animals thrive.

Currently Samburu live in many ways, modern and traditional: still living in traditional hut villages and shepherding, or living in modern homes and holding every conceivable type of job from office worker to high government positions. Monique’s childhood was at a pivotal transition point as the culture first grappled with incoming modernity. The issues she struggled with are still a struggle in a great many families, especially for the most remote and poorest families, and for women and girls, who often still face enormous misogyny, abuse, FGM, and forced marriage.

A traditionally-attired boy watching cattle. Shepherding may also be done by girls, but is typically reserved for boys and young men of pre-elder status, including the famous moran, warriors. Samburu main herds historically were cattle, but also commonly include goats, sheep, and recently, occasionally camels. Image credit: Andreas Lederer, CC BY 2.0 license

The Samburu are less well-known than the southern Maasai, as during the colonial period the British sequestered the Samburu’s home territory (along with the Turkanas and many other “troublesome” endlessly warring tribes in the west and north) in the Northern Frontier District: a giant “time out” zone cut off from other Kenyans and the outside world. This kept them more isolated than other groups outside the NFD. Samburu County only started getting a real “flow” of people and ways in and out after Kenya’s Independence in 1963. Hence the Samburu were among Kenya’s last groups to start “modernizing.”

Samburu women constructing a traditional hut, with everyday-wear finery on AND a young child. The traditional society structure has women and girls doing the vast majority of the work with very little say in their lives; while the boys and men, responsible for defense and leadership, have much leisure time and nearly all the power. Image credit: Dr. Ondřej Havelka (cestovatel), CC BY-SA 4.0 license

Samburu culture is ancient, clearly rich in heritage and skill for surviving via the Old Ways. Their society is traditionally rigidly organized, with definitively set roles by age and gender. These especially caused Monique and other girls and women a lot of difficulties, as traditional society strictly controls women and girls, seeing them as mainly supports–or commodities–for men, and for raising children and doing most of the village labor. Modern Samburu women have often faced great struggles if they aspire to a different life path, such as many of Kenya’s other modern women pursue.

A view of a partially constructed traditional home inside a manyatta, a village. Women build all these homes. A thorn fence encircles the outside, both to deter predators coming in and livestock escaping. Image credit: Filiberto Strazzari, CC BY 2.0 license

A regal elder woman in Wamba, one of the towns featured in Monique’s stories. The brown mporro necklace signifies her married status. It is made from giraffe tail hair, palm frond fibers, red beads, and rubbed-on ochre: the local rust-red dye made from iron-rich earth mixed with ghee or animal fat. Her attire is entirely traditional, except for her inclusion of a modern t-shirt underneath. Monique’s beloved great-grandmother Nkooko looked similar, except darker-toned and even more lovely, elegant, and stately. Image credit: Collines Omondi, Pexels free-to use license.

An elder man journeying. Note his tire sandals and colorful shuka shawl, just as described in the book. Akuyia looked much like this on his four-day walks to visit Monique and her family: except Akuyia again was darker and favored a hat, in the small bowler style, and did not have any paved roads to travel on. Image credit: Peter Godfrey, Pexels free-to use license.

Young “morans,” or warriors. Their lives are full of great privilege and also many restrictions. They are in charge of protecting the livestock and village. Every warrior intake group–spaced 14-15 years apart–has its own age-set name, and the warriors are extremely close with other members of their moran age-set. Image credit: “Young Samburu male,” by Sankara Subramanian, CC BY 2.0 license

Samburu women at a festive occasion. They doubtless made all this finery themselves, along with other villagers. Having to work as much as women do, they generally only wear full regalia on special occasions, stripping down to their most prized simpler pieces for everyday wear. Image credit: “Samburu women” by Sankara Subramanian, CC BY 2.0 license

An elder man carving. Note his colorful shuka, shawl. The elders of both sexes are generally afforded much freedom, leisure time, and respect. Elder men in particular hold the most power in the society, and traditionally take many wives. Morans are traditionally forbidden from marriage until they retire from moran-hood after their 14-15 year “service” and receive junior elder status when the next age-set is initiated. Image credit: “Samburu Man Carving Wood,” by Filiberto Strazzari, CC BY 2.0 license

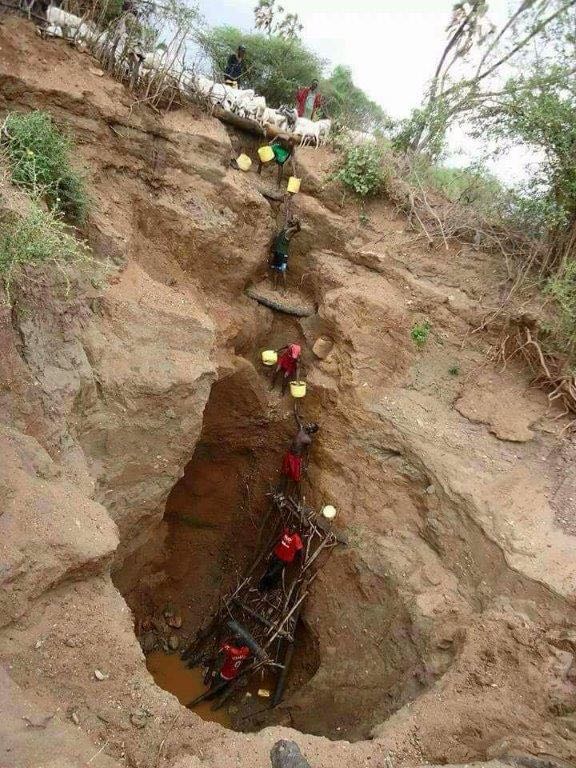

Fetching water from a water hole. As you see, this can be quite an endeavor. In this instance these are men fetching water for their livestock (at the top). For village and home use, the water is generally fetched by children (usually girls) or women, as Monique endlessly–and dramatically–had to do in her stories. Many villages now have access to piped water, but many still do not. All rivers in Samburu County regularly dry up, except the Ewaso Ngiro on the far county border. Knowing where water holes exist and how to use them, and seeing the signs that water is present underground to dig new holes, are essential skills without which the Samburu and their livestock would have perished long ago. Image credit: Ous732,, CC BY-SA 4.0 license

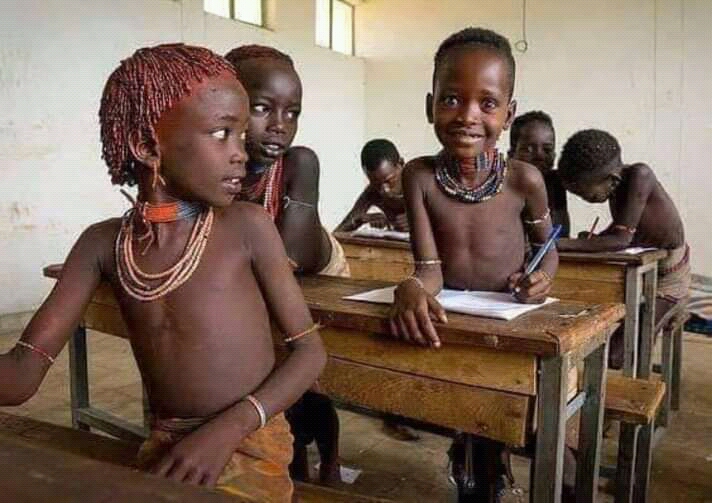

Samburu secondary school girls in uniform, I believe in Wamba, the distant-from-Maralal town that Monique’s aunt went to secondary and married in. This is a different school than Monique went to, and the uniforms are much lighter than her primary uniforms were. Both private Catholic schools and government schools, day and boarding, are popular choices, and make a tremendous difference in the lives of their students, especially-notably being the best protection for girls against early forced marriage. Image credit: “WGSS Faith“, Alaina Buzas, CC BY 2.0 license

Young boys in a non-uniform primary school. The boy in the front is sporting the traditional twisted, ochred hair, while the others have more modern short styles. If front-row-boy keeps twisting his hair as he grows, by the time he is a moran it will fall far down his back, like the warriors in this page’s header image. Image credit: Moses Mwombe, CC BY-SA 4.0 license

This young girl is wearing more modern attire, as Monique generally did: except that Monique preferred t-shirts over button-ups. Note the baby on her back. From young, girls shoulder an incredible amount of child care and village/household labor responsibilities, just as Monique did. The boys with her are unencumbered. Image credit: Alaina Buzas, CC BY 2.0 license

The joy of youth! Samburu boys are expected to help with herding and perhaps some basic chores, but they generally have a very free childhood. Image credit: “Running Samburu Boy,” Erik (HASH) Hersman, CC BY 2.0 license